James Chevous

James Chevous James was born 28th March 1877 in Burham, just outside Rochester and was the son of William and Sarah Anne Chevons who lived at 112 Victoria Street Gillingham. All the men in his family were general contract labourers and James sought employment at the Cliffe Powder Works sometime around 1911. Whilst working at the Powder Works he stayed with his niece in Turner Street, Cliffe.

James had been a Royal Marine and has served between 1895 & 1899 when he was discharged “invalided”. However, when war came in 1914, he re-enlisted and joined the crew on the HMS Cressy which was then stationed at Chatham Dockyard.

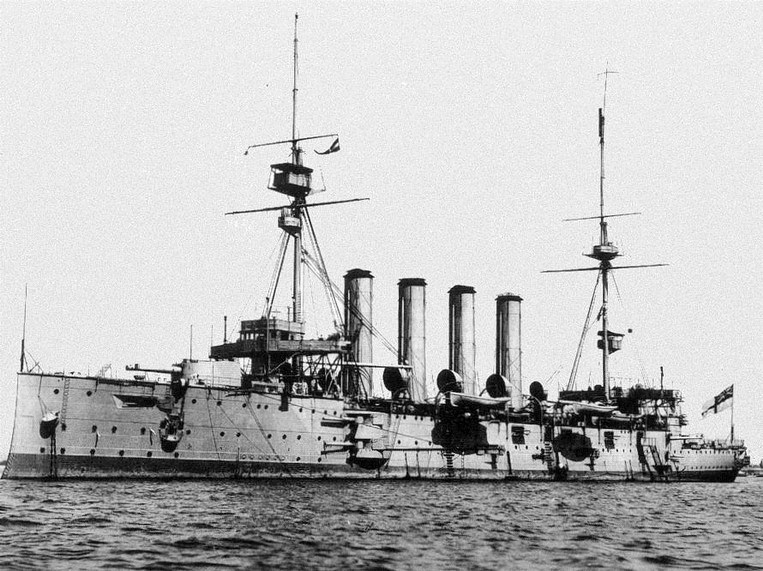

HMS Cressy

The fate of James on the HMS Cressy, together with HMS Hogue and HMS Aboukir, is reported below.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in August, 1914, Cressy and her sister ships Bacchante, Euryalus, Hogue and Aboukir were assigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron, patrolling the Broad Fourteens of the North Sea, in support of a force of destroyers and submarines based at Harwich which blocked the eastern end of the English Channel from German warships attempting to attack the supply route between England and France.

The Cressy class had been placed in the Reserve Fleet. No money was to be spent repairing them, but they were to be used until they were completely worn out. In 1914, the best speed they could manage was 15 knots. Each ship had over 700 officers and men from the Royal Navy Reserves, many being middle aged family men from local towns and villages. Each ship also carried nine cadets from the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, most of whom were under 15.

The original plan was to support the destroyers of Reginald Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force, but frequent bad weather caused the plan to change and the cruisers became the front line as they could handle the rough seas. After weeks of daily patrols, their old engines could no longer even maintain 15 knots and speed dropped to 12 knots, and often as low as 9 knots and, because they never sighted periscopes, they no longer zigzagged.

On 17 September, in rough seas, the destroyers were sent back to Harwich. On 20 September Rear-Admiral Arthur Christian returned to port with HMS Euryalus to coal, reducing the patrol to three ships, Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue. With Christian unable to transfer his flag, command devolved to Captain John Drummond of the Aboukir. They continued to patrol as the weather improved until sunrise on 22 September.

At 6:20 AM on September 22, HMS Aboukir was torpedoed by U-9 and sank in 35 minutes. Thinking she had struck a mine, and sinking fast, the order was given to abandon ship. Hogue and Cressy approached to pick up survivors, throwing anything that would float into the water for the survivors to cling to. At 6:55, Hogue was struck by 2 torpedoes. U-9 dived and remained submerged. At 7:20, Cressy sighted a torpedo track, and the order was given "full speed ahead both", too late. Cressy was hit forward on the starboard side, and lurched high enough out of the water that a second torpedo passed under her stern. At 7:30, a third torpedo hit Cressy on the port beam, rupturing tanks in the boiler room and scalding the men. Cressy rolled to her starboard side, paused, and then went bottom up with her starboard propeller out of the water. She remained in this position for 20 minutes, and then sank at 7:55. Unfortunately for Cressy, her boats had been sent to pick up survivors from the other 2 ships, and returned already loaded with men. As many as 5 men clung to a single life vest, and a dozen men to a single plank. Dutch fishing trawlers were in the area, but remained at a distance until 8:30 when the steamship Flora from Rotterdam arrived and rescued 286 men. The survivors were almost all naked, and so exhausted they had to be hauled aboard with tackle. The steamer Titan rescued another 147 men, and later 8 of Tyrwhitt's destroyers arrived. All told, 837 men were rescued, but 1,459 men were lost.

The "Live Bait Squadron"

On 21 August 1914, Commodore Roger Keyes (commanding a submarine squadron stationed at Harwich) wrote to his superior Admiral Sir Arthur Leveson warning that in his opinion the ships were at extreme risk of attack and sinking by German ships because of their age and inexperienced crews. The risk to the ships was so severe that they had earned the nickname "the live bait squadron" within the fleet. By 17 September, the note reached the attention of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill who met with Keyes and Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt, commander of a destroyer squadron operating from Harwich, while travelling to Scapa Flow to visit the Grand Fleet on 18 September. Churchill, in consultation with the First Sea Lord Prince Louis of Battenberg, agreed that the cruisers should be withdrawn and wrote a memo stating:

“The Bacchantes ought not to continue on this beat. The risks to such ships is not justified by any services they can render.”

Vice Admiral Frederick Sturdee, chief of the Admiralty war staff, objected that while the cruisers should be replaced no modern ships were available and the older vessels were the only ships that could be used during bad weather. It was therefore agreed between Battenberg and Sturdee to leave them on station until the arrival of new Arethusa-class cruisers then being built.

Most of the men on board these ships were from the Chatham Division and many of the men on board were local men. When news reached Chatham vast queues of relatives waited for news of their loved ones.

James Chevous was amongst the 1459 men lost at sea: his body was never recovered.

James Chevous was amongst the 1459 men lost at sea: his body was never recovered.

A site dedicated to one of the largest naval disasters in world history and to the memory of its 1459 British victims. It happened close to home on the North Sea, 22 September 1914, exactly seven weeks into the First World War.