EXCAVATIONS ON THE ROMANO-BRITISH INDUSTRIAL SITE AT BROOMHEY FARM, COOLING

by Alec Miles and reproduced by kind permission of the Kent Archaeological Society.

Eight years of emergency excavations in advance of deep ploughing on farmland at Cooling revealed an almost complete Romano-British industrial site (NGR TQ764/767) dating from the first to early third centuries ad. The excavations which were undertaken for the Lower Medway Archaeological Group over the period 1966-1974, uncovered a large wedge-shaped mound on the first-century saltings, which showed evidence of hut foundations, salt-boiling hearths and pottery manufacture; also further evidence for other mounds built up on the Roman saltings over a wider area. Information gained from the excavations will be of wide significance in resolving many longstanding problems posed by the Romano-British settlements of the North Kent marshes of the Thames and Medway.

The excavated area is on the Thameside Marshes, being part of a site possibly covering an area of 1.5ha; further occupation extends to the higher ground on the south comprising Thanet Sand with the odd patch of Woolwich Beds, currently occupied by pear orchards. The site, on land belonging to Broomhey Farm, is some 1.2km north-east of St James Church, Cooling, between two spurs that jut out into the marshes, Northward Hill to the east and Cliffe village to the west. The post-Roman rise in sea-levels has resulted in the deposit of some 0.3m of silt over the highest parts of the mounds; however the building of the sea-wall nearby in Medieval times protected the site from further silting.

The site has a long history of finds. The earliest reference is in the Numismatic Chronicle (vii (1867), 7) which records a denarius of Gordian III and Tranquillina. The next reference to the site comes in Archaeologia Cantiana (XLII, 1930, xlviii), where R.F. Jessup reported a mound of friable soil, irregular patches of burnt material, a quantity of the poor pottery called briquetage and occasional fragments of a more substantial fabric. The burnt material proved to be pieces of the stem, leaves and root of a species of rush (Juncus). Among the pottery fragments were burnished black sherds of soft fine clay ornamented in La Tene fashion with cordons, and pieces of rough gritted red ware which may be perhaps referred to the culture of Hallstatt.

Three years later, a further report Arch. Cant. (XLV 1933, xliii), states that: ‘On land at Cooling belonging to Fred Muggeridge, whose excavations have previously revealed considerable quantities of pottery, a Roman kiln and two skeletons were recently uncovered’. Mr Cook reports ‘That as the graves had been cut through the layer of burnt clay and pottery debris surrounding the kiln, it is evident that the pottery was in disuse before the date of the earliest burial, which seems to be about the beginning of the second century AD. The cemetery consists of cremations and inhumations’.

In 1936, Maidstone Museum’s gazetteer records that a local newspaper stated that nine more kilns were discovered and that pottery and briquetage from the excavations was in the Museum. In several conversations held with Fred Muggeridge before his death in 1972, further details were given. He stated that when excavating the first kiln, which was contained in a mound, a rush floor was found. Later excavations had uncovered more kilns in a row, on the slightly higher ground of the pear orchard just off the marsh (TQ 765/766); these kilns were presumably those mentioned in the newspaper report. They were not destroyed but re-covered with soil and pear trees planted between them.

More information was recovered from a series of glass photographic negatives taken in the 1930s and currently located at Rochester Museum, Maidstone Museum and Eastborough Farmhouse, Cooling. These photographs are all of the first major kiln find, showing it in varying stages of excavation. They show a permanent type of updraught kiln with a solid floor with the well preserved remains of the shallow dome, the loading vent visible at the top (Swan 1984, 35, pi.4). One glass negative shows Roman pottery dating from the first and third centuries arranged around the kiln, including pottery from the adjacent cemetery and other excavations in the immediate area. In 1979 RCHME photographed the entire collection.

The site was re-located in 1966 as part of a wide ranging study of the Romano-British occupation sites (Miles 1975, 29-39) in the North Kent Marshes. On learning that within a few years the site would be deep ploughed and drained prior to changing the land use to arable farming, it was decided to undertake an emergency excavation. It was believed that the protected position of the site, safe for centuries behind the medieval sea-wall, would enable valuable and important evidence to be collected of the likely similar nature of the many other

Romano-British sites in the marsh and on the saltings which have already eroded away. The difficult conditions met on many sites washed by the tides meant that very little serious work could be attempted and accurate information was lacking.

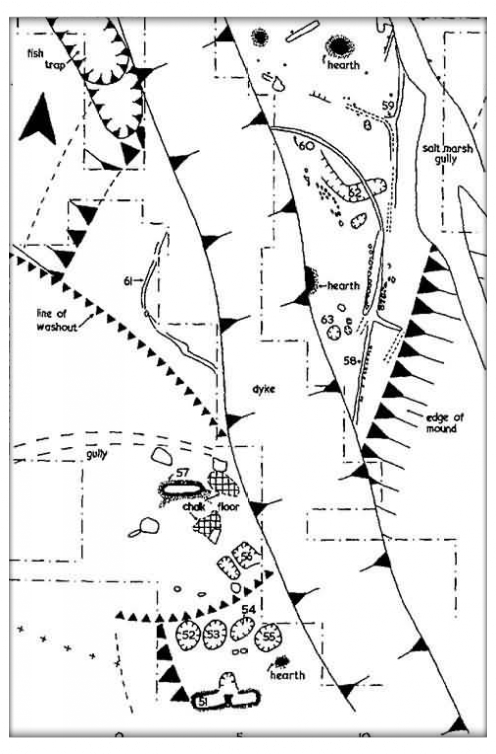

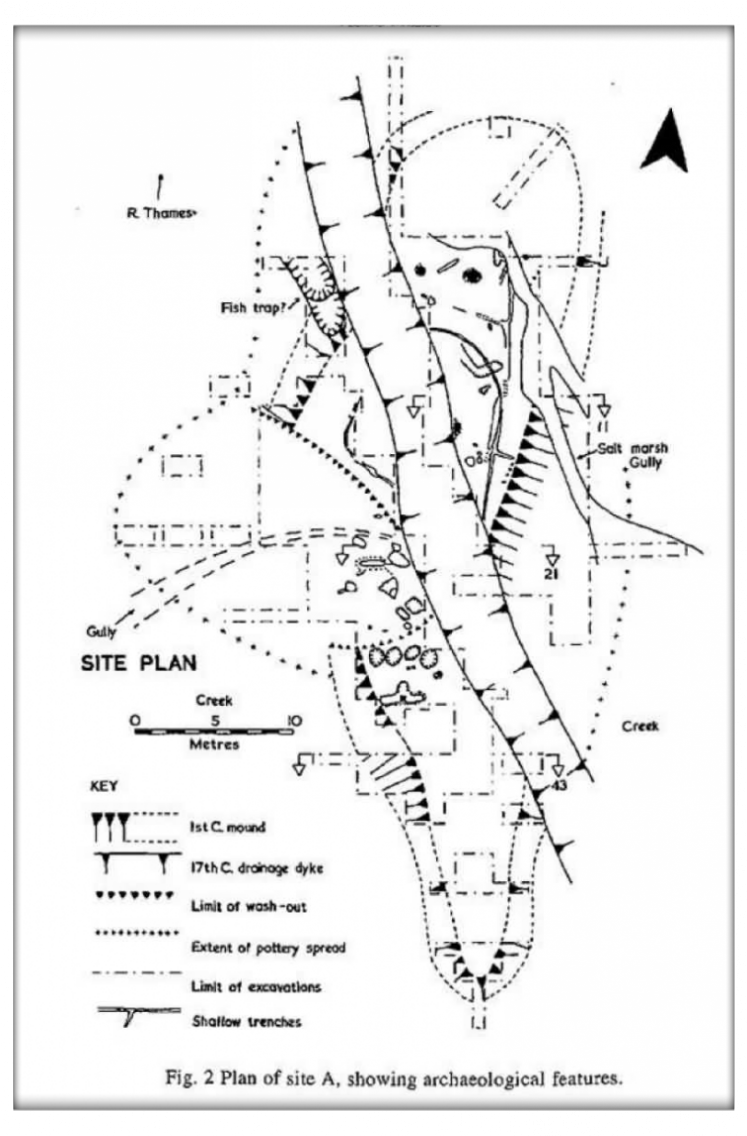

Trial trenching was initially undertaken in 1966 to attempt to locate the sites of previous excavations and discover where it was best to lay out the new. Most trial holes showed signs of the previous excavations. However, a small trench on a low mound to the west of the site revealed, immediately below the topsoil, a rammed briquetage floor with a line of stakeholes flanked by a foundation trench. It was decided to centre the excavation around this feature [Site A]; between 1967 and 1973 an area of around l,650m2 was excavated.

In an attempt to uncover the previously located kiln a series of trenches were dug at a point [Site B] 22m east of site A, where high proton-magnetometer readings and photographic evidence suggested a likely site. A further series of trenches were dug at [Site C] where trial trenching had revealed kiln debris and first-century pottery.

A major difficulty encountered was the high water table, which varied from just under the surface in mid winter to an average of 1.5m below in mid summer. Excavations were taken to a maximum depth of 4m (13ft) below the marsh surface or nearly -2m (-7ft) OD, this being some 5m (16ft) below high water, mean ordinary tides. In fact normal excavation practices were used throughout, pumps being used to keep the water just below the working levels, leaving the marsh clay damp and not allowing it to dry out.

Site A

Phase 1

The original mound was thrown up in the first century on the pre-Roman saltings standing at around +lm OD (compared with present day saltings outside the sea-wall which attain a level of c. +3m (Evans 1953, 111), overlaying a reed bed. The mound was some 52.4m long varying from 11.8-3.3m wide, curving slightly to the east, rather reminiscent of a seawall; however, there was no evidence to support the making of a Roman wall, but traditionally it was thought locally, that the early sea-wall followed the line of Whalebone Marsh; while the old west creek eventually led, via Buckland Fleet, to Decoy Fleet and Egypt Bay, possibly a distance of some 5.63km. The mound tails away southwards to a possible causeway leading to the higher ground, but careful excavation showed no traces of this and would suggest it had been eroded by high tides sometime in the past. The west side of the mound had been open to the tidal estuary and suffered erosion from storm surge tides especially in the second century. On the east side of the mound, an old creek showed signs of silting up and was later filled with pottery refuse.

The main activity in the first century was salt-making with twin hearths [51] with a common stokehole: (1) 114.3cm long by 45.7cm wide inside and 14.2cm deep; (2)

106.6cm long by 48.2cm wide inside and 15.2cm deep. Later an oval hearth was superimposed over (2), 106.6cm long by 45.7cm wide. Four brine tanks of the first century, situated just to the North were: [52]oval shaped, 109.2cm x 91.4cm and 22.8cm deep; [53] circular 99cm in diameter, and 30.4cm deep; [54] oval, 111.7cm x 91.4cm and 33cm deep; [55] oval, 121.9cm x 99cm and 35.5cm deep.

To the north of the salt-boiling complex the remains of first-century rectangular huts were uncovered, delineated by drip trenches [58], lined with sheep or goat bones. The floors were mainly of crushed briquetage. In the later second century a large storage jar [63] was inserted in one of the floors with a bowl and a dish inside, with a small sand lined pit with bones of a human baby nearby. A number of quern fragments were also recovered from this area consisting of Mayen Lava, Millstone Grit, Puddingstone and stone from the Folkestone Sand. The presence of sheep or goat bones along with cheese wrings suggests that the saltings were used for grazing; certainly in early medieval times sheep grazed the open saltings, not without some risk from flooding by the sea (Evans 1953, 144-45).

Phase 2

Into the second century, evidence from the presence of briquetage would suggest that salt-making continued, while pottery-making of shelly ware was a minor activity in adjacent areas. By this time erosion of the mound by the sea, possibly under storm conditions, meant that the mound was repaired by the dumping of clay, briquetage and pottery waste, while the later pottery refuse and domestic rubbish, among which was a loomweight and a large flat pottery kiln- bar were used to partly fill the east creek. There is some evidence for revetting of the mound by stakes at this stage. Towards the north-west corner of the mound was a pit dug in the Roman foreshore with a filling of shells of Cardium edule (cockle); Mytilus edulis (mussel); Littorina littorea (edible marine shell); Macoma baltica (small bivalve); and also Cepaea memoralis (L) with Hygromia hispida both

terrestrial molluscs. Mr Morris of the British Museum, who identified the molluscs, has suggested that the marine specimens were trawled with a rake as they do today in South Wales, where large and small specimens are gathered indiscriminately and kept in the possible fish tank, possibly cleaned out on a regular basis. Also in the pit, along with vegetable matter were numerous second-century miniature pots, possibly of a votive nature. However, first-century pottery was also found in the pit so it could have been open for a considerable time. In the north-east corner traces were found of rectangular huts [59], although post-Roman erosion of the site by the sea had obscured most of the traces.

Phase 3

By the later second century into the early third century, pottery- making was the main occupation with the mound extended some 36.58m wide to the west with pottery waste, while the East Creek being some 3m deep likewise filled with pottery waste and no longer open to the sea. Among this waste was pottery with a metallic glaze (cf. Fig. 10, no, 92). During this period the West Creek was still open to the Thames Estuary and the sea, allowing pottery, salt and agricultural products to be shipped to distant markets.

Phase 4

Salt-making was continuing with a hearth [57], 129.5cm long x 91.4cm wide and 25.4cm deep, with at least four phases of rebuilding. The latest phase being 81.2cm long x 32cm wide with walls of the hearth vitrified with a green salt-glaze, this does not indicate a high temperature as the presence of salt acts as a flux and lowers the melting point of clay. Chalk foundations roughly 60.9cm square suggested a hut, 2,47 x 2.47m over the hearth.

Nearby rectangular brine tanks were excavated, they were [56], 95.2cm long x 68.5cm wide and 27.9cm deep, 106.6cm long x 91.4cm wide and 25.4cm deep. Possibly other tanks were washed away. A third- century flanged bowl with the flange chipped off was found inside one, adjacent a small pit filled with coal (also found in occupation layers towards north-east corner of mound). A drip-trench of a circular hut [60/61] 1 lm in diameter was uncovered. Some evidence for pottery making continuing after the main production phase finished is found in pottery of the later third century found in a shallow trench [59].

Final phase

By the end of the third century all occupation and industrial activity had ceased and the site reverted to open saltings, with rilles cutting through the site. The evidence for the final reclamation of the marsh is shown by the cutting of a drainage dyke straight through the Roman mound, possibly in the seventeenth century as a pipkin handle of that date was recovered from the base of the dyke. Strangely enough no traces of this dyke can be seen on the surface of the present day marsh, but it ran parallel with an existing dyke. Tradition has it that the Dutch were responsible for the reclamation of Cooling Marshes, but there is no documentary evidence for this, although the Dutch polders today are drained mostly by parallel dykes. According to Bowler (Bowler 1983, p. 29) there are few records before 1690 for the North Kent area.

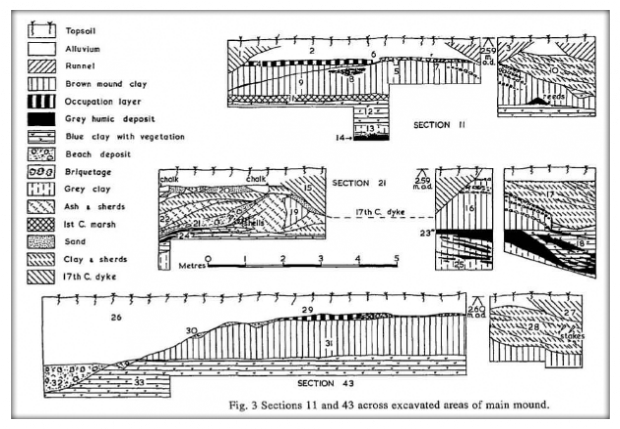

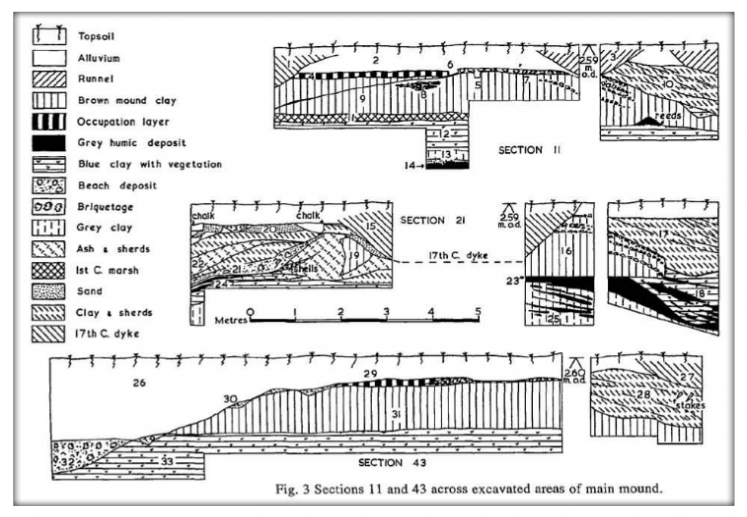

Sections of the Main Mound

The pre Roman saltings at Cooling are typical of those found outside the seawall today, made up of mature and immature saltings cut up with creeks and rilles and in parts eroded away by the tides. It was difficult to find a section which showed the full sequence. [Horizons shown in cm below]

Section 11 (A-B), squares 12-1-11. Elevation 2.59 metres OD.

0-61 Stiff alluvial clay, hardly any topsoil (2).

61-71 Black Romano-British occupation layer, first to third century, showing foundations of hut [4] mainly of crushed briquetage with layers dipping to East creek, underlain by a timber foundation slot [6].

71-162 Brown mound clay [5] (10YR 5/3), originally blue clay in which the reduced iron compounds have oxidised on exposure to air, with deposit of goat or sheep bones [8] inserted.

162-78 Brown pre-Roman mature saltings [11] with a decalcified top-layer of 2.5 cm with the seeds of the annual sea- blite (Suaeda Maritima), an efficent silt trapper along with sea aster in the formation of saltings (usually found below high-water mark Spring Tides).

178-224 Thick blue clay with streaks of vegetation and scraps of briquetage [12].

224-244 Grey clay [13](5Y 4/1).

244+ Dark humic layer [14].

Western sequence, shows 17th-century drainage dyke with infill of stiff clay to 127cm deep [1].Section 21 (C-D), squares 4-17-21. Elevation 2.9m OD. Shows good section of East creek towards east of section.

0-30 Top soil and clay 30-152 Mound clay [16].

152-93 Peaty sludge layer dipping into base of creek? Pottery/ clay fill of East creek [17].

Western sequence mainly in ‘washout’ shows remains of mound [19] eroded by the sea, with layers of sand [20], beach deposits, with specimens of Phytia myosotis (Drap.) [21] (which lives on rotting vegetation near high watermark) and ash [22], underlain by peaty layers [23] and blue clay [24] with reeds and underlain by grey clay[25] at 2.70m.

Section 43 (E-F), squares 43-52. Elevation 2.6m OD 0-51 Topsoil and clay [26].

51-71 Occupation layer with briquetage [29].

71-168 Mound clay [31].· 168+ Blue clay with increasing indications of reeds [33].

Site B: the Saltern Site

This site was located by a proton-magnetometer survey of the area where Muggeridge excavated the kiln in the 1930s, in the hope that further kilns would be found. In an area of high magnetometer readings, nine 2.43 x 2.43m squares were excavated under extremely adverse conditions caused by the constant flooding of brackish water, presumably from an old creek. Although two pumps were operating continuously to pump out the water, it was not possible to excavate the squares fully. The squares were dug to a max, depth of 2.28m. In the case of squares K7 and K8, it was possible to excavate through layers of briquetage, clay, wood ash and earth to a layer of brown clay with root channels down to the surface of the blue clay with reeds, presumably the surface of the pre Roman mud flats. K1 was on the edge of a deep creek, while K2 was a jumble of layers of briquetage and clay, diving vertically into the creek at a depth of 2.28m. No signs of hearths or any other structures were found and doubtless these were elsewhere. The site was obviously a Romano-British industrial rubbish tip, with much pulverised and fragmented debris from the salt-making operations dumped into the open creek with access to the open sea of the Thames estuary, during the period 60-100 AD. The site plan and sections are deposited in Maidstone Museum as an archive; along with the coarse wares and small finds.

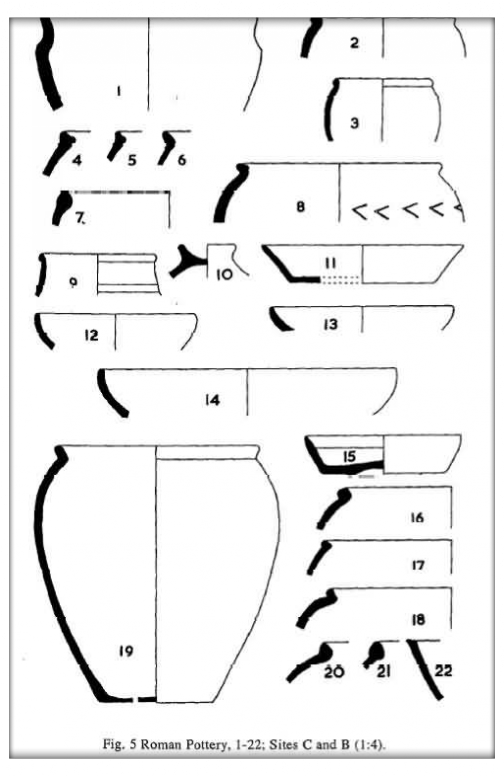

1. Rough hand made bowl scratched IIIVI on rim. Buff, grog- tempered. AFC/K9, cf. Monaghan class 4D1.5; first-century.

2. Bead-rim jar, hard grey ware shelly ware. AEQ/K4, cf. Monaghan class 4E2.2; 70-110.

3. Bead-rim jar, hard grey sandy ware. AFJ/K2, cf. Monaghan class 3E1.2, Upchurch; 10-100.

4. Bead-rim jar with recessed rim, rough grey hard shelly ware. ADY/K4, cf. Elliston Erwood 1916, no. 43; first-century.

5. Bead-rim jar similar to above. ADX/K6; first-century.

6. Butt-beaker, burnished on outside, wheel made, sandy fabric. ACZ/K6, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, Form 112; middle first century.

7. Native bowl, in hard rough pink sandy ware. ACZ/K6; first-century.

8. Lid seated jar, black handmade, with chevron decoration on shoulder, hard rough shelly ware. AFJ/K2; first-century.

9. Jar, black ware burnished on outside, hard sandy ware. K8, cf. Bushe-Fox 1925, Swarling no.17; not earlier than first half of first century.

Site B. First-Century possible Bonfire Kiln area Middle to late first century.

10. Lid, red sandy ware, grey interior, scored with fine lines outside. Above kiln debris. AJA/T2; first-century.

11. Platter, in sandy grey ware. AKC/T4, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, Fig. 47, no. 13; 50-60.

12. Platter, sandy grey ware, burnished inside. AHC/T2, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, form 17; 40-60.

13. Platter, grey pink sandy hard ware. Under hearth debris, AHN/T2, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, form. 17; 40-60.

14. Platter, grey pink sandy ware, burnished on outside. AHJ/T2, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, form 17; 40-60.

15. Platter, black smooth hard sandy ware, burnished on outside. Mussel bank, AHO/T2, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, form 13; 40-60.

16. Bead-rimmed jar with square bead, rough hard sandy ware, slightly shelly. AGX/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3E7.2; 30-70.

17. Bead-rimmed jar, red scored ware, rough hard and shelly, AJA/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3F3.2, Cliffe; 70-120.

18. Lid-seated jar, fine scored hard black/grey ware, slightly shelly Mussel bank, AHO/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3L3.1, Cliffe; 70-140.

19. Hooked bead-rim jar, orange vesicular shelly ware with three holes in base. Under hearth debris, AHI/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3F3.4; 45/50-70/90.

20. Hooked bead-rim jar, bead pinched to point, hard rough ware sparse sand and shell. Hearth debris, AHN/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3F4.2, Cliffe; 70-140.

21. Bead-rimmed jar, soft red shelly ware. Hearth debris, AHN/T2, cf. Elliston Erwood 1916, no. 46, first century, Charlton earthworks.

22. Dish, hard pink vesicular ware, slightly shelly. AKE/T5; first-century.

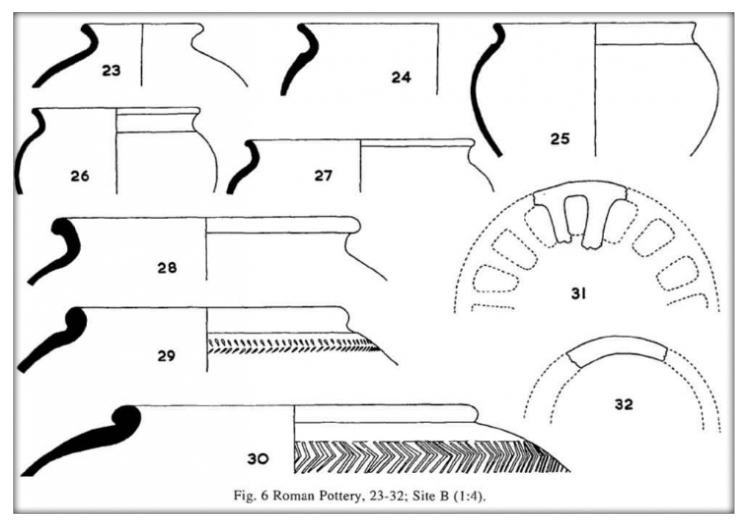

[Fig. 6]

23. Narrow mouthed jar, pink red sandy ware, burnished outside and inside neck. Under hearth debris AHI/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3B3.1; 50-100.

24. Deep bowl with out turned rim, hard sandy pink ware, burnished inside rim and 5cm down on outside. Mussel and ash layer, AHH/T2, cf. Monaghan class 4D4.1; 50-70.

25. Bowl with everted rim, pink ware. Below hearth, LP/T2, cf. Monaghan class 4D4.1; 50-70.

26. Bowl with everted rim, burnished inside and outside rim, pink hard sandy ware. AJE/T2, cf. Hawkes and Hull 1947, form 221; 40-50.

27. Bowl with everted rim and slight bead, pink hard sandy ware, burnished rim. AHH/T2, cf. Monaghan class 4D0.1; 40-60.

28. Large wide mouthed storage jar, hard sandy burnished ware. AIE/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3D 1.3, Cliffe foreshore; 40/50-150.

29. Storage jar, pink sandy ware, with stabbed decoration on shoulder. AGH/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3D4.2, Cliffe; 40/50-150.

30. Storage jar, pink sandy ware, with chevron decoration. AHH/T2, cf. Monaghan class 3D2.1, Cliffe; 40-150.

31. Kiln spacer, circular plate with perforations, 11mm thick. Soft pink shelly ware. AIE/T2, 40/50. Unique.

32. Kiln spacer ring, top side broken off, 8-10mm thick. Hard pink sandy ware. AGL-AIE/T2; 40/50. Unique.

Main ‘Mound SiteOccupational and Industrial Layers

Middle first century to third century. (Fig. 7)

33. Dish, pink sandy handmade rough ware. Lower black ash, SV-RQ/21, cf. Monaghan class 5E4.3; 50-70.

34. Dish, black hard hand made sandy ware, burnished on outside. Beach layer, SP/21, cf. Monaghan class 5E4.2; 50-70.

35. Platter with beaded rim ,hard smooth grey ware almost no temper. RT/21, cf. Monaghan class 7A2.4, Upchurch; 43-120/140.

36. Dish, brown/grey sandy fabric. Three notches on rim, ‘X’ on inside of base. DN/6, cf. Monaghan class 5E1.5; 170/190-210/230.

37. Dish, grey crude handmade sandy ware with scribed decoration. QX/21, cf. Kelly, 1992, no. 55; second-third quarter of third century.

38. Dish, brown/black rough sandy handmade ware. First-century mound, AHY-AHV/48; first century.

39. Dish, sandy hard grey, burnished outside. In gully, TC/21, cf. Monaghan class 5D0.2, Upchurch; 120-150/180.

40. Dish, pink, sandy, roughly burnished. Red floor, TR/29; first-century

41. Dish, decorated, with rolled rim, black burnished pink sandy ware. Under beach, VG/28, cf. Monaghan class 5D1.5, Cliffe; 110/120150/180.

42. Dish, rim turned over, triangular profile, black burnished with dense black slip, repaired with bitumen. Fish-pit, AKJ/76, cf. Monaghan class 5D2.5 Cliffe, Canterbury defences; 150/180.

43. Dish, plain, orange, burnished and slipped, sandy. Black ash floor same level as hearth, AAE/39, cf. Monaghan 5C1.2; 170/190-220-230.

44. Dish with lattice decoration, hard burnished black sandy ware. Base layer, RQ/21; 150-180.

45. Dish with downward rolled, over hanging rim, slipped and burnished. Pink with grey core hard sandy fabric. Above red floor, BA/2, cf. Monaghan 5C4.3, Upchurch; 150/180-250.

46. Dish, grey hard sandy ware, burnished and slipped. East creek, AJM/57; second/third-century. Unique.

47. Dish, orange , handmade burnished and slipped, decorated, sandy. East creek, KW/12, cf. Monaghan 5C0.4; 170/190-210/230, unique.

48. Cheese press, perforated sides and stabbed decoration, grey coarse sandy ware. On red floor NE sq 18, black floor UX/28, cf. Detsicas 1977, first-century pottery manufacture at Eccles, in Dore and Green 1977, no. 97.

49. Dish, grey sandy coarse ware, hand made, perforated sides, grey throughout. Top layers, QY-AGV, sqs 21/48, second/third-century. Unique.

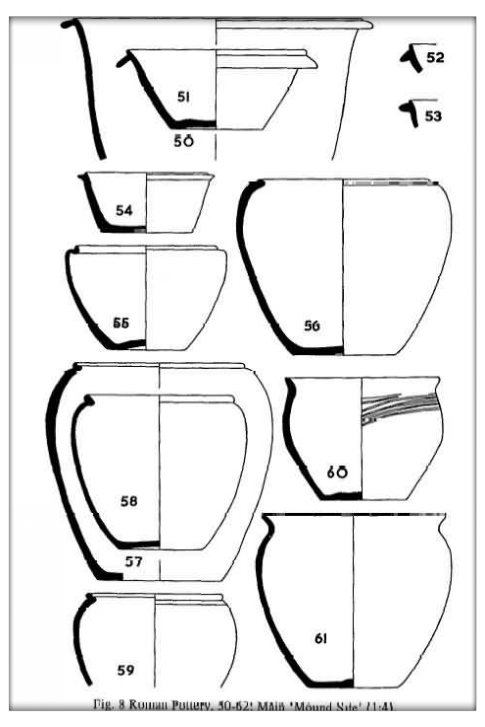

50. Bowl, grey thin flange with traces of burnish, sandy ware. Shallow trench, KD/11, cf. Monaghan 5A2.2; third-century.

51. Flanged bowl, grey sandy ware, slightly burnished. Brine tank, XD/33, cf. Monaghan 5A5.2, 180/200-320/350; third-century.

52. Flanged bowl, grey, burnished slipped on outside and just inside. Above pebble floor, AI/3, cf. Monaghan 5A5.1, Upchurch; 180/200. 53. Flanged bowl, grey, burnished, sandy. Top of east creek, JK/14, cf. Monaghan 5A4.2, Upchurch; 200/240-320/350.

54. Flanged bowl, triangular flange, black sandy ware, no burnish. ABY/40, top layers, cf. Pollard, in Catherall 1983, no. 23 at Oak Leigh Farm, Higham; 220-240.

55. Facetted bead rim jar, fine combed black/red ware, shelly/sandy. AAK/21 base, cf. Monaghan 3G1.2, Upchurch; 40-70.

56. Facetted jar, grey combed ware, shelly/sandy, some burnishing at base. AAK/36, in gully, cf. Monaghan 3G5.5; 50-70.

57. Lid seated bowl, very fine combed sandy ware. AKI/76, fish pit base, cf. Monaghan 4L2.2; 50/70-90.

58. Hooked bead rim, grey unburnished sandy ware. ZD/38, brine pit, cf. Monaghan 3F3.2, Cliffe; 70-120.

59. Bead rim bowl with recessed rim, black ware, burnished around rim. Lower black SV/21, cf. Elliston Erwood 1916, no. 43 Charlton earthworks, first-century, Monaghan 4L2.2; 50/70-90.

60. Jar with simple out-turned rim, black, handmade with black slip inside rim. AAK/36, in gully, cf. Monaghan 313.2; 40-70.

61. Wide mouthed everted-rim jar, pink burnished outside and some burnishing inside sandy ware. QW/RN 21 top layers, cf. Monaghan 311.2; 10/20-70 (common).

62. Not illustrated, similar to no. 60, smaller, AAK/36 gully; 40-70.

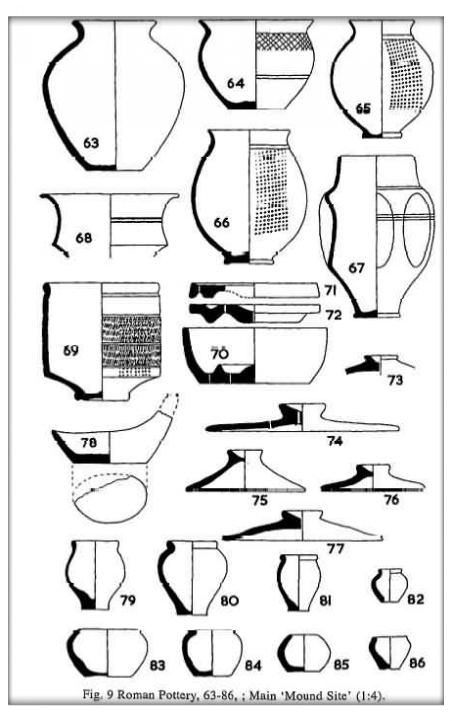

63. Narrow mouthed jar, orange grey orange, slightly burnished on shoulder, sandy. ZD/38 early brine tank, cf. Monaghan 3B1.1; 50/70 100.

64. S-profile bowl, black ware, burnished half-way down, slipped inside rim. AAK/36 beach layer gully, cf, Monaghan 4A1,7; 50-70 (common). 65. Poppyhead beaker, grey Upchurch ware, burnished 6mm inside rim. VI/22 blue clay under washout, cf. Monaghan 2A2.4, Upchurch; 80/ 90-120.

66. Poppyhead beaker, grey Upchurch ware, burnished, slipped and mended with bitumen at rim. AJV/58 fish pit, cf. Monaghan 2A3.2, Upchurch; 100/110-130/150.

67. Folded beaker with funnel neck, black, burnished to first cordon and slipped to third cordon, sandy. VJ/28 top layers, cf. Hull 1963, form 407; third/fourth-century.

68. Carinated beaker, black, not burnished or slipped. Fine ware UF/28 bottom layers. Cf. Bushe-Fox 1932, no. 292; first-century.

69. Girth beaker, burnished, rouletted and barbotined. Fine paste. ZF/38 early brine pit, cf. Monaghan 2F3.1, Upchurch; 90/130.

70. Cheese wring, orange, hand made and knife trimmed, black slip, sandy ABS-RV/39-38 brine basin/lower washout; 50-70, cf. Monaghan 1 OB 1.1 Cliffe; 70-200.

71. Cheese wring lid, black ware, slipped, burnished, sandy. U/S, cf. Monaghan 10A1.1, Cliffe; 70-200.

72. Cheese wring lid, black ware, slipped. WA/31 below chalk floor, cf. Monaghan 10A1.1, Cliffe; 70-200.

73. Lid, rough grey ware, sub angular quartz. WP/31 Yellow clay, cf. Monaghan 12B1.1, Cliffe; 50-100.

74. Lid, hard ware with black slip inside, hand made with coarse combed decoration, sandy. Core: grey. FY/3 upper red layer, cf. Monaghan 12F1.2 Upchurch; 70-140.

75. Lid, grey with coarse combed decoration, sandy. AJN/58 fish pit, dating as above.

76. Lid. red-brown coarse ware, slip inside lid, sandy. TC/21 bottom ash over gully; dating as no.74.

77. Lid, rough grey ware, no decoration. VC/21 under beach; dating as no.74.

78. Crude lamp, rough fabric, sandy. RQ/21 base layers; 50-70.

79-80. Fine miniatures based on jar forms, grey, sandy, quartz. AKK/76 137cm, deep in fish pit; late second-century.

81. Fine miniature, grey, sparse sandy. East creek PG/14, Monaghan 9B3.1, 170-230.

82. As above, un-stratified.

83. Miniature, jar form, cindery fabric. Fish pit, AKL/76, cf. Monaghan 9A3.1; 50-70.

84. Miniature, handmade coarse, sandy rough pink fabric as fig. 83. Washout, QW/21; 50-70.

85-86. Miniatures, rough pink sandy fabric with some grog. Fish pit AKL- AJR/76, cf. fig. 83, Monaghan 9A3-9A3.4; 40-70.

Main Pottery Phase 180-220

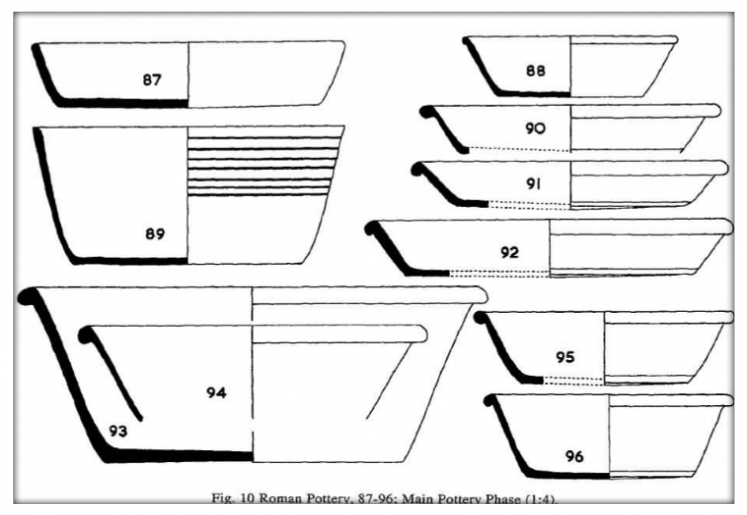

Sand tempered ware. Pottery waste layers. (Fig. 10)

87. Simple ‘dog dish’. Ext. black: Core grey: Int. black. Burnished and slipped, with vestigial chamfer. Traces of white pigment. AKP/8 from large storage jar, cf. Monaghan 5E1.1; 130/160-260.

88. Dish, grooved. Ext. brown: Core black: Int. brown. Burnished and slipped, vestigial chamfer. East Creek FM/3.

89. Dish, sandy ware, multiple grooves. Ext. brown: Core grey: Int. brown. Not slipped. Pottery waste layers, ABH/40, cf. Monaghan 5F0.3; 170/190-210/230.

90. Dish, rolled rim, grey slightly sandy, narrow chamfer, burnished and slipped. East creek FW/4, cf. Monaghan 5C3.2; 150/180-250.

91. Dish, downward rolled. Ext. brown: Core grey: Int. brown. Burnished and slipped, with chamfer. East creek HIM, cf. Monaghan 5C4.5; 150-180-250.

92. Dish, downward rolled. Ext. grey: Core. Grey: Int. grey. Almost metallic sheen, burnished and slipped with chamfer, abundant. East creek PM/14, cf. Monaghan 5C4.5; 150-180-250.

93. Dish, rolled rim with rounded profile. Mostly grey, sandy surface, not burnished and not slipped, rare. Late layers K2/11. cf. Monaghan 5D1.6; 110-120/150-180 (perhaps later at Cooling).

94. Dish, rolled rim, with rounded profile. Ext. brown: Core grey: Int. brown. Burnished and slipped. East Creek FW/4. Monaghan see above.

95. Dish, rolled rim with rounded profile. Ext. red: Core Black: Int. red. Burnished and slipped, chamfer. East Creek HIM, cf. Monaghan 5D1.7, Shorne; 110/120-150/180.

96. Dish, downward rolled, over hanging rim. Ext. brown: Core grey: Int brown. Burnished and slipped with chamfer. East creek FW/4, cf. Monaghan 5C4.4; 170/190-210/230.

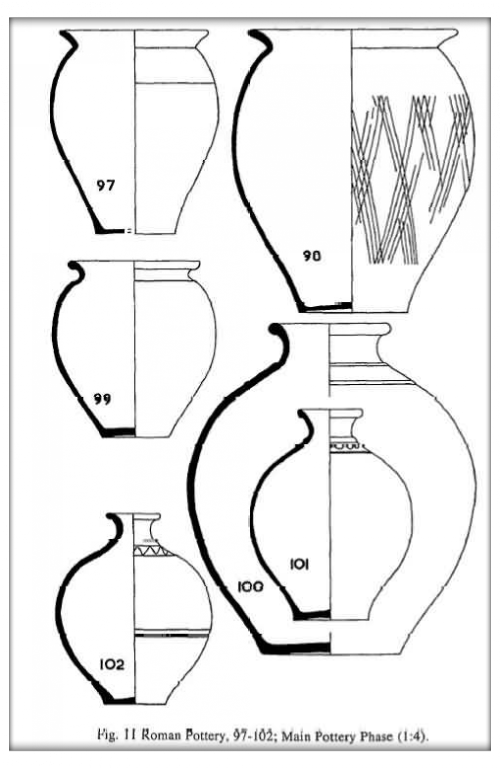

[Fig. 11]

97. Jar, with narrow base and splayed rim. Ext. dark grey: Core grey: Int. dark grey. No decoration, burnished and slipped around rim, abundant. Kiln waste layer ABE/40, cf. Monaghan 3 J9.1; 170/190-210/230.

98. Jar, with narrow base and splayed rim. Ext. dark grey: Core, grey: Int. dark grey, Lattice decoration, burnished and slightly slipped around rim and inside, several examples. Kiln waste layers ABH- ABD/40, cf. Monaghan 3J9.2; 170/190-210/230.

99. Everted rimmed jar. Ext. dark grey: Core grey: Int. dark Slightly burnished and slipped, over 10 examples. Kiln waste layers ABH/40, cf. Monaghan 3H1.5 Upchurch; 100-200.

100. Narrow necked jar, grey ware, sandy feel, with neck cordon no burnish or slip, fine grey quartz. Kiln waste layers ABH/40, cf. Monaghan 3 A3.2; 170/190-210/230.

101. Flask with cordon, wavy decoration. Ext. dark grey: Core grey: Int. dark grey. Part slipped and burnished, sandy feel. Kiln waste layers ABH/40, cf. Hull 1963, form 281; 170/190-210/230 (common).

102. Flask with cordon. Ext. brown: Core grey: Int. brown. As above. Kiln waste layers ABH/40. Number of versions.

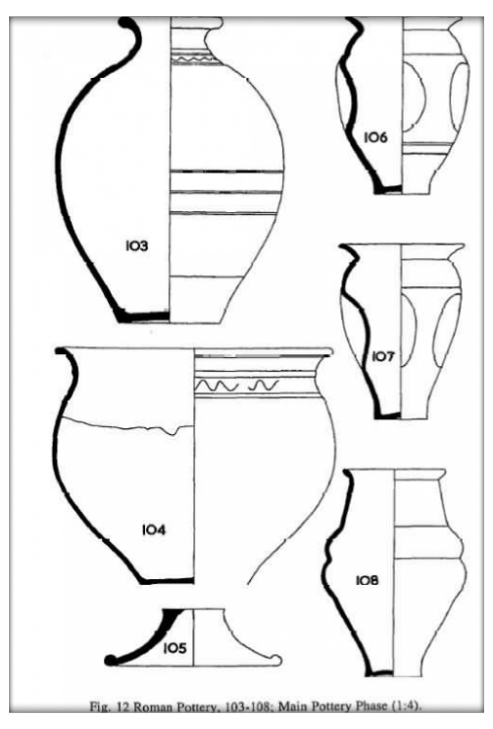

[Fig. 12]

103. Narrow necked jar, wavy decoration. Ext. pink: Core grey: Int. pink. Burnished inside rim. Kiln waste layers ABH/40, cf. Monaghan class 3A5.1; 170/190-210/230.

104. Bowl, Cordoned with wavy decoration, grey/pink, fine sandy fabric partly slipped and burnished. Kiln waste layers ABH/40, cf. Monaghan class 4A2.6; 170/190-210/230.

105. Lid, with upturned rim. Ext. red: Core grey: Int. red. No slip or burnish, fabric rounded quartz and sparse flint. Top of East creek HB/3, cf. Monaghan class 12C2.3; second/third-century.

106. Folded beaker, with flaring neck. Ext. silver grey: Core grey: Ext. black. Burnished to shoulder, slipped. Top of east creek PT/14, cf. Monaghan class 2D2.2; 190/200-220/230.

107. Folded beaker with re-curved rim. Ext. black: Core grey: Int black. Burnished and slipped outside and inside rim. Kiln waste layer ABH/40, cf. Kelly 1992, fig. 7; first half third century.

108. Funnel necked beaker, with constricted body, burnished to shoulder and inside rim. Ext. black: Core grey: Int. Black. Kiln waste layer ABH/40, cf. Monaghan class 2C8.1; 170/190-210/230.

[Fig. 13]

109. Funnel necked beaker, squat and globular, grey ware, slightly oxidised, burnished outside. Kiln waste layer ABH/40, cf. Monaghan class 2C6.4; 170-230. Four examples.

110. As above, rather more bulbous form, burnished and slipped. Kiln waste layer ABH/40. cf. Monaghan class 2C6.1; 190-210/230.

111. Bag beaker, neckless form, burnished. Ext. dark grey: Core grey: Int. dark grey. Kiln waste layer ABH/40, cf. Monaghan class 2E0.1; 180-230.

Cooling Exotica by Jason Monaghan

List of identified exotic fabrics by context:

Hadham (third century) AJX/67 (pebble floor),BA/2 (red floor), MC/14 (east dyke top).

Oxford (third century) MD/11 (topsoil), NE/18 (red floor), JF/11 (top RB), HW/6 (east dyke top), KW/12 (top layers east dyke), WT/31 (east dyke), KC/11 (shallow trench), AJR/58 (fish pit), WY/33 (topsoil). WW/32 (red layer), AAX/39-38 (just above hearths), AAH/39(black ash), KV/15 (briq layer).

Nene Valley type (second-century - later parts) JP/16 (topsoil), DL/6(east dyke), KE/11 (top RB layers),DS/6 (top east dyke), LI/6 (deep east dyke), HE/5 (circular hut trench?), CC/1 (red floor), HC/ (below red floor), AHX/B (site in next field), JG/11 (top black), AIZ/58 (above black), ZY/39 (topsoil), XV/34 (top layers), UK/28 (lower red). Brockley Hill (60-120) unstratified.

Essex Coarse Wares (second century?). AAE/39 (top floor),AHM/57 (top floor).

Colchester Colour Coats (second-century). WW/34 (top layers), JK/14 (top east dyke), NT/20 (top layers), (thin and thick red), DE/4-FQ/3- NC/ 20-GR/6 (top east dyke), KQ/12 (east dyke), ZA/34 (hut circle), XZ/38- ZY/39 (topsoil), BQ/2 (chalk rubble floor), CD/3 (over pebble floor). Rhenish (second century) AFS/46 (dark clay, GS/6-MC/14-JX/16 (east dyke top), ABH/40 (kiln refuse layers),TX/28, WF/32, ZY/39 (top layers. Central Gaulish (first century). AFS/46 (dark clay),GR/6 (top east dyke), KC/6 (top east dyke), ABH/40 (kiln refuse layers), EV/4 (east dyke). Negative evidence: No Mayen, Argonne, Eponge, Rettenden, i.e. late third and fourth centuries. Very little grog tempered Belgic, i.e. pre-invasion. BB2 dishes type 5d, i.e. pre 180 ad and BB2 dishes type 5a, i.e. third century and later were rare.

Samian Pottery

The first listing was undertaken by Jason Monaghan in 1984, then in 1986 Christopher St. Breen compared it to the Dartford District Archaeological Group’s Samian fabric/form collection. Close examination made it clear that a series of corrections could be made. Joanne Bird was also involved at this stage, providing the summary of the 70 fragments of samian recovered (see below). The bulk of these is from the tip layers of the east creek. A detailed archive report is deposited in Maidstone Museum, while the samian and other exotic wares have been deposited with the DDAG’s reference collection at Dartford.

Top east creek:

Central Gaulish Form Dr.24/25 not later than 70 ad ; Forms Dr.31, 18/31, 37 and Form Walters 80, later second century; and Form Rheinzabern 36, later second to mid third.

Lower east creek:

Central Gaulish Form Dr,27 many, late first and early second century; Form Dr.30 Antonine; Form Dr.31R mid second century-Antonine; Form Dr.33 Hadrian-Antonine, also one sherd probably Argonne Form Dr.36 mid second century-Antonine; Form Dr.37 late Hadrian- Antonine; Form Dr.30 (stamped) 150-170 and Form Dr.30 Decorated 120-140.

Red floor sq 19.

Central Gaulish Form Dr.72 mid second century; Central Gaulish Forms Dr.31R, 33, 37, mid to late second century; East Gaulish Form Dr.45 and Form Curie 23, later second to early third.

Foreshore pit.

Central Gaulish Forms Dr.27, 18/31, 31, 36, early second century- Antonine.

Kiln refuse layers.

Southern Gaulish Form Dr.27 later first century; probably Argonne Form Dr.36 later second century; Central Gaulish Forms Dr. 18/31, 31, 36, 37, Antonine.

Hut trench.

Rare form-ribbed bottle-AGZ, on red floor, sq 55 top layers, Central Gaulish, Antonine (cf. Stanfield, J.A., 1929, Unusual Forms of Terra Sigillata’, Arch. Journ., 86, 113-150, fig. 6 illustrates several).

Decorated Samian (not illustrated) by Guy de la Bedoyere

1. Form: Dr.30 Context QN/PO Feature: East dyke. Stamped in the mould by Cinnamus of Lezoux. The boar, both bears and all three stags are on S&S pi. 163,66, the hound on PI. 163,74, the ovolo and beads on pi. 162,56. The leaf may be part of larger one. C.AD 150-170.

2. Form: Dr.37 Context BD Feature: East dyke. Ovolo, beads and heads in the style of Butrio, Central Gaul, 120-140 AD. (note similar; is the style of Libertus) Lezoux, here the ovolo, border and masks as S&S pi.60,679; seated Venus as pi.58,661.

3. Form: Dr.37 Context PI Feature: East dyke. Central Gaul. Ovolo (Rogers B77) used by several unnamed Lezoux potters; the scroll suggests links with the Sacer- Cinnamus Group. Later Hadrianic-early Antonine.

4. Form Dr,37 Context: FT/AFG Feature: East dyke/Top East dyke. Ioenalis of Les Martres-de-Veyre, Central Gaul, Vine scroll, as Stansfield and Simpson, pi.41,477 and 483, which shows similar birds pecking at the grapes. C. AD 100-125.

5. Form Dr.37 Context: FT (separate bowl from 4.) Feature: East dyke Ioenalis of Martre-de-Veyre, Central Gaul, Ovolo and beads as Stansfield and Simpson, pi.33, 416. c. AD 100-125.

Note: two further sherds that may relate to bowl (4). Context: AJX Rubble Floor and Context: GS East dyke Top. Form: Dr.37, from same bowl and same decoration unit (ROGERS M7) but not this panel (4).

The Trade with Northern Sites

This has been discussed by Monaghan at some length, who examined the assemblage from thirteen frontier sites (Monaghan, 1987, 211). He estimated that 50% of the BB2 fabric examined there was Kentish, in particular the fabric from Cooling, Cliffe and Shorne. At the Antonine fort at Camelon, roughly 40% of all the pottery was BB2. Half of the sherds were certainly Thameside produce, most of the remaining ones differing by only a small degree, the most common fabric was from Cooling and Cliffe. The pottery from Carpow, one of the few sites where undecorated pie dishes occurred, was similar to those of Cooling, cf. Fig. 10, no. 90 (5C3 Monaghan 1987, 141).

John Gillam, also examined the pottery from Cooling and recognised it as occurring on many northern sites, especially the fabrics with a slight metallic burnish on the surface, cf. fig 10, no. 92 and fig. 12 no. 106. He noted that this pottery showed up in the ‘destruction layer’ at Carpow (Wright, 1974, 28992) 215-216 AD, also pre ‘metallic ware’ at Benwells (plain rimmed bowls with wavy decoration). Gillam, suggested the export of BB2 started around 180 and ended before 240-270. The flanged rim bowl see fig. 8, no. 50, of early third-century date may represent the later phase of the industry at Cooling. The ABD/ABH layers possibly representing the ware for local markets in the early third century (John Gillam pers. comm.).

Williams has considered ‘that by the late second century or early third a number of small kilns in Kent including Cooling were supplying BB2 to northern military garrison sites’ (Williams 1977). He made a petrological analysis of the heavy minerals of the Cooling fabric comparing it with the fabric of the Northern sites. Salt-production could well have been linked to the export of pottery up the East Coast to the Northern Army. Production started in the first century and continued into the early third until the pottery trade had ceased.

A certain amount of coal was revealed in the excavations. The source may have been the Northern coalfields (although Somerset coal cannot be excluded).

THE BRIQUET AGE

The excavations produced large quantities of briquetage with much fragmentary material being discarded, although many incomplete pieces were retained, these being the remains of rectangular and circular vessels, rectangular and circular plates, wedges and firebars. The fired material varied in colour from dull red to dull purple, presumably reflecting the amount of firing received. A small quantity of slag was recovered. Close examination of the fabric with a 20X lens, showed no signs of grog, flint or quartz, only of organic temper, typical of the Thameside and Medway estuaries material.

J.R.B. Arthur studied organic material from evaporating vessels of the Medway saltings and found it consisted mainly of rye (Secale cereale L)\ probably this was left over from thatching. It is assumed that the alluvial clay was the basic material used by the briquetage makers.

Site B Squares Kl-9

Of the 34 briquetage fragments, 32.3% of the material consisted of rectangular vessels, ranging in thickness from 10-14mm while the remains of oval or circular vessels made up 8.8% of the total, being some 10-18mm thick, (cf. Miles 1965, Fig. 4, 1 and 2). The greater bulk was of firebars, 35.2% being 12-30mm thick (cf. Fawn, Evans, McMaster and Davies 1990, p. 13, fig. 12.) The wedges, of various shapes and sizes were some 13~30mm thick and formed 23.5% of the total (cf. Miles 1965, Fig. 5, 5 and 6). Very little pottery was found associated with this site, and a first-century date is suggested.

Site A. Main Site

The salt-making activity would seem to range from the first century to the early third. Of the 38 briquetage fragments retained, 42% were from rectangular vessels 10-14mm thick, forming the bulk of the material while 39.4% consisted of the remains of oval or circular vessels, 10-18mm thick. A number of rectangular and circular plate fragments were found, these being anything from 8-20mm thick. These consisted of flat fragments where the edges met roughly at right angles and the remains of fragments with a curved edge. It is not known for which purpose these would be used; they made up 13% of the total recovered (cf. Fawn, Evans, McMaster and Davies 1990, pi. 13, RH152, Tollesbury).

Only one fragment of a vessel 20mm thick was recovered, this may reflect different system of heating the brine solution, with larger evaporating vessels spanning the hearths, without the need for kilnbars which were possibly used as horizontal supports for the vessels which rested on them in earlier phases of the industry. Mention must be made of a fragment of a ‘pig-trough’ vessel 26mm thick, found in the supposed ‘fish pit’ just off the main site on the foreshore.

OTHER FINDS

Glass Bead (not illustrated) by CM. Guido

Large cobalt blue glass bead with bosses decorated with opaque yellow spirals (possibly linked with sways in the same colour). Diam. 23mm, ht. 21mm, perforated diam. 8mm. Related closely to the many Oldbury type beads in this country, clearly one of the Celtic late La Tene III beads. A variant comes from Spilsby, Lincs., with sways; also found at Camulodunum.

These beads reached Southern England in some quantities in the latter first century BC and particularly in the South-East (Oldbury, etc) and they linger on into the second century occasionally as survivals in later deposits. Their origin on the continent is possibly Bohemia and they are found in Celtic oppida, which came to an abrupt end in the last twenty years of the first century BC.

Quernstones (not illustrated) by R.W. Sanderson

Compared with material of known origin in the Institute of Geological Sciences collections:

Specimens AB and AE: Feldspathic sandstone. These two specimens appear by their pink colour, to have been burnt. However, they are probably examples of Millstone Grit, possible from Derbyshire or south Yorkshire.

Specimen AA: Amygdaloidal tholeiitic basalt. The writer has been unable to trace comparable material in IGS collections. As such rocks occur in many part of the area of Roman influence, precise origin cannot be given.

Specimen AC: Glauconitic sandy limestone: This compares well with specimens of Bargate Stone from Godalming and Midhurst. Only possible to suggest a source in the western Weald.

Specimen AD: Glauconitic cherty sandstone. A specimen of Hythe Beds from near Larkfield (Maidstone) is similar to this. The differences (less green colour and slighter grain size) are not important enough to warrant suggesting a more distant source.

Coal Samples from Cooling and Cliffe by A.H.V. Smith

The samples produced reasonably rich assemblage of microspores, the composition of the two samples was different due to the fact they were derived from coals of differing petrology. However certain stratigraphically useful species were recognised. These species indicate that both coals are of Middle Coal Measures age widespread in the British coalfields but when the rank of the samples is considered it is possible to restrict the coalfields of origin to those of South Wales, Bristol and Somerset and Durham. A knowledge of the methods and the routes by which the Romans used to transport coal in Britain may eventually suggest the most likely source. The provenance of the coals from some overseas coalfield cannot be excluded although the measures in the Pas de Calais coalfield , the nearest to Kent, are entirely concealed.

Anatomical Report on Baby Skeleton by J.P. Hayes

The following bones were identified:-

Skull.

Large part of (L)frontal bone - 2 adjoining fragments.

Large part of both parietal bones. More of the (R) than of the (L) was present. The (R) consisted of 5 adjoining fragments, the (L) of 3.

Squamous part of (L) temporal bone more or less complete.

Both zygomatic bones more or less complete. The (L) articulates with the frontal bone.

Posterior half of (R) mandible.

Anterior half of (L) mandible.

1 incisor tooth.

20 other fragments Of skull bone some of which fit together.

Rest of axial skeleton

4 vertebral bodies.

6 neural arches. 4 (R) thoracic, 1 (L) thoracic, 1 (L) cervical.

12 ribs or rib fragments. 6 (R) 2 (L). The rest were too incomplete to place. The 1st and 2nd ribs on the (R) were identified.

Upper limbs

Medial two thirds of (R) clavicle.

Both scapulae. The (R) was broken across the blade and partly missing.

Both human

The upper ends of the (L) ulna and radius.

No bones inferior to thoracic vertebra or belonging to the more distal parts of the upper limbs could be identified.

Two bone fragments were also present which fitted together and formed part of a long bone from a much older individual - possibly an adult. The general morphology of the bones especially that of the skull identify them as human. The shape and size of the bones point to their being those of a new-born baby.

Goat/Sheep bones from body of mound by J.E. King

Metacarpal

Radii - left and right

Humerus, I frag. L and R

Scapula frags

2 Tibiae L and R 2 Femora L and R

1 Pelvis frags plus a number of vertebral fragments and rib fragments. These bones are all very young and are certainly from the same animal.

B.2. Many small bones including foot bones and limb bone fragments and epiphyses. Also vertebral and rib fragments. These bones are probably from the same animal as above.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Permission to excavate was readily given by Mr F. Muggeridge and the farmer Mr M. Bucknall and we are grateful to them both for their kind co-operation and assistance over the years.

The 1966-74 excavations were jointly undertaken by the author and M.J. Syddell, who later emigrated to Australia, Hence the report was written up by the author, who takes full responsibility for any deficiencies. The excavations were financed by a grant from the Kent Archaeological Society and a donation from P. A. Oldham (who gave continuous support throughout). Thanks are due to The Council for Kentish Archaeology for the loan of a Pegson Marlow pump.

The writer’s thanks are also due to members of the Lower Medway Archaeological Group and other volunteers who helped with the excavations. He is particularly indebted to Miss J. ICearsey, Messrs. F. Delaney, S.J. Dockrill, P.A. Harlow, M.J. Jessup, W.J. Morement,

D.J. Robertson and D. Wraight, who all worked very hard under adverse conditions. He is grateful for the work undertaken by J.P. Hayes in restoring the pottery; also to D.B. Kelly, and V.G. Swan, for help and advice with the pottery; R.D. Green, for help with the soil profiles; E.J. Philp for identifying ‘molluscs’ and M.A. Ocock and T. Ithel for undertaking site surveys and levels, while Daphne Miles helped in many ways particularly in proof-reading the draft of this report.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowler, E., 1983, ‘For the Better Defence of Low and Marshy Grounds: A Survey of the Work of the Sewer Commissions for North and East Kent, 1531-1930’, in A.P. Detsicas and N. Yates (eds), Studies in Modern Kentish History, KAS, Maidstone, 29-48.

Bushe-Fox, J.P., 1925, Excavation of the late Celtic Urnfield at Swarling, Kent (Rep. Res. Comm. Soc. Antiq. London 5).

Bushe-Fox, J.P., 1932, Third Report on the Excavation of the Roman Fort at Richborough, Kent (Rep. Res. Comm. Soc. Antiq. London 10).

De Brisay, K., 1978, ‘The excavation of a Red Hill at Peldon with some notes on some other sites’, Antiq. Journ., LVIII pt.l, 31-60.

Detsicas, A.P., 1977, ‘First Century Pottery Manufacture at Eccles, Kent’, in J. Dore and K. Greene (eds), Roman Studies in Britain and Beyond, BAR 19-36.

Devoy, R.J., 1980, ‘Post-glacial Environmental Change and Man in the Thames Estuary: a Synopsis’, in F.H. Thompson (ed.), Archaeology and Coastal Change, The Society of Antiquaries of London, 134-48.

Dore, J. and Toomber, R., 1998, National Roman Fabric Reference Collection, Museum of London Archaeology Service, 166.

Elliston Erwood, F.C., 1916, ‘The Earthworks at Charlton, London S.E.’, Journal of the Brit. Arch. Association (new series), xxii, 125-91.

Evans, J.H., 1953, ‘Archaeological Horizons in the North Kent Marshes’, Archaeologia Cantiana, LXVI, 103-46.

Farrar, R.A.H., 1973,‘The Techniques and Sources of Romano-British Black-Burnished Ware’, in A.P. Detsicas (ed.), Current Research in Romano- British Pottery, Research Report 10, CBA, London, 67-103.

Fawn, A.J., Evans, K.A., McMaster, I. and Davies, G.M.R., 1990, The Red Hills of Essex, Colchester Archaeological Group.

Frere, S.S., Stowe, S., and Bennet, P., 1982, Excavations on the Roman and Medieval Defences of Canterbury (The Archaeology of Canterbury, Vol. II), Maidstone,

Gilham, J.P., 1973, ‘Sources of Pottery found on Northern military Sites’, in A.P. Detsicas (ed.), Current Research in Romano-British Pottery, Research Report 10, BAR, London, 53-62.

Green, R.D., 1968, Soils of Romney Marsh, Soil Survey of Great Britain, Bulletin No. 4, Harpenden, 8.

Hawkes, C.F.C, and Hull, M.R., 1947, Camulodunum (Rep. Res. Com. Soc. Antiq. Oxford 14).

Kelly, D.B., 1992, ‘The Mount Roman Villa, Maidstone’, Archaeologia Cantiana, CX> 175-235.

Miles, A., 1965, ‘Funton Marsh salt-panning site’, Archaeologia Cantiana, LXX, 260-265.

Miles, A., 1968, ‘Romano-British salt-panning hearths at Cliffe’, Archaeologia Cantiana, LXXXIII, 272-273.

Miles, A., 1975, ‘Salt-panning in Romano-British Kent’, in K.W. de Brisay and K. A. Evans (eds), Salt the Study of an Ancient Industry, Colchester, 26-31.

Monaghan, J.,1987, Upchurch and Thameside Roman Pottery: a Ceramic Typology, first to third Centuries A.D. (BAR(B), no. 173).

Pollard, R.J., 1983 ‘The Coarse Pottery, including the Kiln Products’, in P.D. Catherall, ‘A Romano-British Manufacturing Site at Oakleigh Farm, Higham, Kent’, Britannia, vol. XIV,121-38.

Pollard, R.J., 1988, The Roman Pottery of Kent, Monograph Series of the Kent Archaeological Society, Vol. V, Maidstone.

Swan, V.G., 1984, The Pottery Kilns of Roman Britain, RCHME, Suppl. Series, no. 5, London.

Williams, D.F., 1977, ‘The Romano-British Black Burnished Industry: an Essay on Characterisation by Heavy Mineral Analysis’, in D.P.S. Peacock (ed.), Pottery and Early Commerce, London, 163-238.

Wright, R.P., 1974, ‘Carpow and Caracalla’, Britannia, v (1974), 289-92.